What has not yet come: On climate crisis, colonialism, displacement, and ancestral inheritance in This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection

by Natasha Thembiso Ruwona

Program

What has not yet come: On climate crisis, colonialism, displacement, and ancestral inheritance in This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection

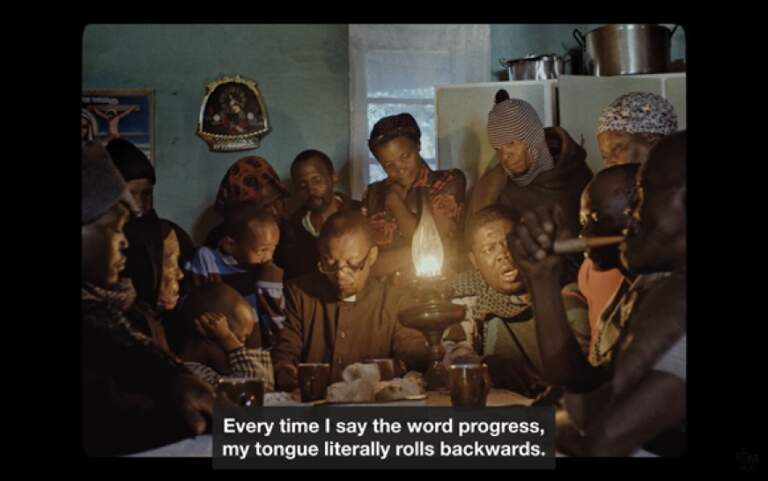

Still from Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese’s This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (2019)

Upon Googling the film’s production country of Lesotho (admittedly I did not know which part of Africa it was situated in) a question appears—“Why is Lesotho in the middle of South Africa?” This question begins the journey of considering the themes of land ownership prevalent in This Is Not a Burial.

Geography pushes and pulls Black communities towards and apart from one another. We can take the Transatlantic slave trade as the most prevalent mode of mass movement and enforced migration to the Americas, while considering the journeys undertaken by Black migrants who risk their lives sailing across waters to reach the United Kingdom and Europe in the hopes of ‘better’ living conditions and opportunities.

And what of water? This Is Not a Burial challenges and highlights the dystopian Western contemplations of climate change and shows that they are already a reality in Africa. Floods and other environmental disasters are destroying African communities, despite those who are impacted contributing much less than the West to the ongoing decay of the planet. Water is a catalyst within this push and pull of movement, destruction, sanctuary and resource.

Writer Katherine McKittrick has done extensive work in the areas of Black geographies and, in particular, Black feminist geographies. McKittrick describes Black geographies as subaltern or alternative geographic patterns that work alongside and beyond traditional geographies and site a terrain of struggle. 1 In This Is Not a Burial, the site of the aforementioned struggle is the village and, more specifically, the sacred burial ground holding the remains of generations of families which is to become a reservoir, a decision made by the government without consulting those whose lives it impacts most. Black lives are by necessity geographically determined; they struggle with discourses that erase and despatialize their sense of place. 2 This Is Not a Burial centres on Mantoa’s struggle over the right to be buried on this land alongside her ancestors, as the village grapples with resettlement due to an imminent flood.

The variations of kinship to the land are apparent as Mantoa fights for why it should be cared for while explaining her own need to be buried there in conversation with a government official whose only concern lies in its utilitarian purpose and modern advancements. The same space is given different meanings and uses pertaining to a psychogeographical understanding of place: ancestral belonging and respect for land exist in opposition to viewing it as something to be built upon and reworked. “Today we’re knocking at the door of the modern world” says the official. The struggle between Indigeneity and modernity is made apparent, as is the not-too-distant memory of the colonisation of Africa for its resources.

Residents of the village voice opposition to these plans by expressing their own relationship to the land, with one man stating during a village meeting with government officials: “I toil on this earth. I feed my family from this earth. The soil is a gift from my mother.” The land is seen as a gift, both metaphorically and physically, given by those who once walked upon it.

Mantoa continues to echo these concerns further on in the film: “I know every single herb that grows in these plains like the back of my hands.” She knows the land as she knows herself, recalling memories and situating the land as it exists within Indigenous practices. “I would dream of herbs that could mend wounds. I have done mixtures that can foretell the future, repel a thunderstorm, summon the rain in dry season.” A generational shift occurs when a young boy begins to grapple with the results of climate change. “I wonder how deep the water is going to be above my head? It’s hard to imagine this place covered in water and fish swimming everywhere.” Could it be possible for humans to breathe underwater? A fetus in its mother’s womb is certainly alive in an aquatic environment. Mother Earth; the umbilical cord.

As the viewer, we wait—for the dam, showers, waters to rise, flood, death—impetus happenings. We wait in silence, with the woman, mourning what has not yet come. We wait knowing.

Natasha Thembiso Ruwona

Natasha Thembiso Ruwona is a Scottish-Zimbabwean artist, researcher and programmer. They are interested in Afrofuturist storytelling through the poetics of the landscape, working across various media including; digital performance, film, DJing and writing. Their current project Black Geographies, Ecologies and Spatial Practice is an exploration of space, place and the climate as related to Black identities and histories. Natasha is interested in different forms of magic and is in particular drawn to the power of the moon.

Natasha completed a curatorship for Africa in Motion Film Festival 2019 and was selected as Film Hub Scotland’s New Promoter for Glasgow Short Film Festival’s 2020 edition. They are a Project Coordinator for UncoverED, Assistant Producer for Claricia Parinussa, a Committee Member for Rhubaba, Board Member of the CCA, and Assistant Curator for Fringe of Colour.