Filming Palestine in the Present

by Azza El Hassan

Program

Filming Palestine in the Present

I once imagined that, inside a film, there was another film. In that film, the victims would win and their image would be transformed. They would not resemble their oppressors and they would not do to others what has been done to them. Instead, they would tour the world and change it into a better one; with no victims in it.

Dream Sequence from Kings & Extras (2004)

The reason I could imagine and construct another film inside a film is because the film I was watching had no images in it. There were only shadows, sounds and fading colors being projected in front of me. It was a film reel that had been left inside a 16mm camera for twenty-two years without being developed. The person who left it was Mosa. One of the cameramen that worked at the Palestinian Film Institute, PFI, in Lebanon.

In 1982, when the Israeli army invaded Lebanon and the PFI was destroyed, Mosa didn’t know where to deposit the film reel, now that the Institute was gone. He eventually left Lebanon and took his camera, with the film reel in it, with him. Mosa was one of my film protagonists in Kings & Extras (2004). I met Mosa in Damascus where he showed me his camera and the film reel that was left inside.

Kings & Extras, was my film about the lost PFI film archives. It was a filmic journey that took me from Palestine to Jordan, to Syria and to Lebanon, as I traced the fates of people who worked in the PFI and who could know what happened to the missing films and photos. In the film, I never find the lost film archives and, before I begin my journey, I play footage that was acquired from the Israeli Film Archive. Palestinian sources confirmed that this footage belongs to the PFI archive, which indicates that the Israelis took the lost archive. Nevertheless, I continue my search, moving from one country to another, meeting people who crossed paths with this lost archive, whether filmmakers, cinematographers or neighbours of the PFI building.

Near the end of the film, in Beirut, Lebanon, I meet a man who lives in the same building where the PFI archive used to be. He confirms that the Israeli army came with lorries and took the archive, but, it becomes irrelevant to confirm what everybody seemed to know from the beginning of the film.

In Kings & Extras, I make my own archive of private and public narratives: of people who experienced loss and their way of coping with this loss. In the film, I trace fables and narratives which were created to cope with the loss of the archive. These are stories that people have experienced. These narratives are akin to the story about a fire that ate all the films preventing the army from getting to them. They are also like the story of the filmmakers in the PFI salvaging their own films and burying them in the Martyrs Graveyard, to conceal them and protect them.

There was a lot that attracted me to the narrative of the first Palestinian visual archive to be created following the Nakba. I went searching for it, just after I lost my own audiovisual archive, during the Israeli invasion of Ramallah city in 2003. In Kings & Extras, Kadijiah Habashnah, the PFI archivist, describes how Palestinian spectators in refugee camps saw the films made by the PFI and the effect of that experience on them:

“They felt helpless, with no power whatsoever, but suddenly on the screen they saw Palestinian fighters. This gave them power and a sense of identity… and they loved it. They loved it.”

They Loved it…. (Kings & Extras, 2004)

After the loss of the PFI Archive, I meet, in Lebanon, a young Palestinian man, who seems invisible. He cannot be seen, except if a spot light and a camera is pointed at him. Yet, there are no longer cameras nor spot lights.

At the end of the film, the images that I imagine to be on the film reel are in fact the very images that I wished to find. It is the desire for these images that has motivated my journey all along. A better depiction of the one that now dominates our reality, and the possibility of a future that is not grim or helpless. It is what I needed and what my film’s protagonists needed. My interest in finding this alternative image was growing and developing with each film I made. I saw my protagonists’ struggle with the roles history had given them and the unbalanced, unjust reality in which they dwelled.

RESISTING THE FRAME

The subject of one of the film sequences in News Time (2001) is my protagonists during the war; this film was shot during the second Intifada (Palestinian uprising, 2000—2005), where the presence of news agencies and cameras in Palestine and Israel matched those in Washington. The daily reality of Palestinians, which included air strikes and invasions, was being televised all over the world. But little attention was being given to how these attacks were impacting people’s personal lives, and their losses.

To emphasise the difference between the image that the average person was seeking and the image the media was depicting, in News Time, I filmed men, women, couples, and children going into a photography studio to get their photos taken, with backdrop scenes of sunset and seashores with blue skies. In these personal portraits, my protagonists—men, women, children and couples—are smiling, and in love. They tend to their appearances before their photos are taken. They want to look good, especially in the moments when they are being filmed, and their images are traveling all over the world.

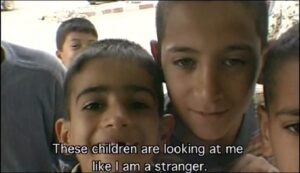

They like to film us… (News Time, 2001)

And yet, the subjects of these personal portraits feel that they capture them the way they would like to be seen: happy, smiling, with friends or in love. This does, however, turn out to be their “poster image”—at their vigilance, as they themselves become yet another causality of the occupation.

News Time is a film that speaks of the problematic relationship between world media and individuals who belong to a society that is struggling with injustice. On the one hand, media attention is needed and it is sought because individuals want to tell their stories. They want the world to know what is happening to them in the hope that the world would finally demand that this situation must end. Yet, on the other hand, the nature of news reporting omits their private narratives, where televised incidents and events rob people from the reality of their narratives. It is this other narrative that News Time attempts to capture.

To escape the general narrative of war and occupation, and to focus on what really matters to people, I decided to film a love story. It is the story of my landlords, Im Khalil and Abu Khalil, who have been together for twenty five years and who have managed through all these years and all the wars to remain in love. Yet, while I am filming, the bombing intensifies, and the lovers decide to flee Ramallah and go to the suburbs, saving their love and abandoning me and my film. My efforts to focus on the personal narrative, the private one was taken over by the general narrative of the war.

To complete what had become a film abandonedby it’s protagonists, I directed my camera to four boys who have continued playing in my neighborhood all through the bombings. This time, I thought innocence should overcome war. Yet, as much as I attempted to focus on what is normal and what should be life, at least in the private spheres of individuals, the problematic reality that is enforced by occupation keeps creeping in, until in the end I lost the four children to the masses who came out to demonstrate against the occupation.

My personal desire as a filmmaker, to find an image and a narrative that escapes the immediate, and offers a depiction of a person dwelling in a war situation, is the theme in News Time and Kings and Extras. This desire is expressed explicitly in In Search for a Death Foretold (2004), where I negotiate my own inability to deal with this problematic reality and my need to leave in order to search for different possibilities. Ones that involve finding images that have gone missing and to connect to the past in order to deal with a present. This video art piece is my prologue for Kings & Extras and is the theme in many of films that would later follow.

In Search For a Death Foretold, 2004

HEALING FROM THE IMAGE

The first time I thought of the need to heal from an image depicted on a film reel, or to heal from the loss of a photo, or a film, was in 2003. A woman asked me to make a film about her so she could deal with her unresolved past. She was angry with her father, Ali Taha, not because he hijacked a plane in 1975, but because he died in the process leaving her young mum with four little girls to fend for themselves.

“You have no right to do that!” said Raeda to my camera as she spoke to her dead father, just after she had shown me film footage of the hijacking and the ambush of the plane. It was obvious that Raeda had played, for herself, this film footage at least a dozen times. She knew every detail of every image. It was as if she was trying to make sense of what she had seen, the event itself and the images of it.

I knew a longtime ago that the process of filmmaking was often a cathartic act, in which I can perform, to deal with the intolerable reality that I was living in. The camera itself shielded me and offered me distance from what was playing in front of me. Yet, this was the first time that I realised that film protagonists who disclose to the camera their inner feelings can engage in their own cathartic act and that the process of assembling, rearranging and viewing themselves can offer a healing process. In 3cm Less (2003), Raeda Taha, not only uses me, my camera and the process of filmmaking to deal with her problematic reality, but anyone else who the camera gets into contact with.

In the beginning of the film, a group of kids are curious about my camera and myself. They do not know that it is a tool, one that they will use, and that I by choosing this tool cannot escape them and that I will let them use me and my camera to organize their world and make sense of it.

They use me (3cm Less, 2003)

Within the space of the film, Raeda exhibits all of her collectables from Ali’s past; his watch and his house door. She follows his previous life before he became a hijacker, when he still worked as a tour guide in Jerusalem. In the film, Raeda cries and laughs.

“Did he not think he could die?” “Did me and my mum and sisters mean nothing to him?” Raeda asks Taraz, Ali’s friend, a woman hijacker who survived the ambush.

Raed confronts her fathers photos and the film footage of the hijacking of the plane on the screen, but also, as she sits spectating the film, she sees his blood on the screen in front of her. “Is this his blood?” I ask in my film’s narration.

Is this his blood! (3cm Less, 2003)

Archive as a memory instigator tool is expanded within the film to include not only photos and films, but also neighborhoods and homes from which the present has been forcefully ejected from. This is the type of archive which I find myself confronted with when I take Raeda to Haifa, after I staged a scene where Raeda meets one of the victims who was on the plane which her father hijacked. This scene was supposed to confront Raeda with her father’s past with which she wants to reconcile. Yet, I found myself instead confronting my own fathers past.

Being behind the camera did not mean that I would not also face my own demons. This is what the city of Haifa does to me. It is the city where father, when he was eight years old, was forced out of and became a refugee. It is a city that embodies all the pain that was engraved on my father’s life and on our family’s life choices. Pointing my camera at Haifa’s landscape brought out all my sentiments towards it. Filming Haifa and later on, editing the images, meant that I could gaze at it’s landscape and revisit my memories of this city, which I visited once before with my father, and saw how vulnerable he was as he stood in front of his family home unable to enter it as it has now been seized by the State of Israel.

Haifa (3cm Less, 2003)

The unsettling relationship with personal archives and the damage it inflicts on the makeup of families is captured through Raeda’s story. It is reiterated in another narrative that runs parallel to that of Raed’sa in 3cm Less. In that narrative, the daughters of Hagar—who is turning eighty—want to celebrate their mother’s life by making a film about her. Hagar had spent her life fighting as she raised ten children on her own. She struggled to bring her husband’s dead body back to it’s hometown to receive a proper burial and to stand against the confiscation of the family land. Yet, as filming commences and the daughters begin to recall their childhood, it becomes apparent that the daughters paid a price for their mothers heroic involvement in the resistance of occupation.

ESCAPING THE PAST

For years, the journey and search which I undertook in Kings & Extras, travelling from Palestine to Jordan, to Syria and finally to Lebanon, is a repetitive journey present in most of my films, sometimes omitting one of the stops and sometimes adding another. It was as if I had lost something along the way and I have ever since been returning to search for it.

Being on the road in my filmic journeys meant that most of the time I was making road movies where the narrative, almost always, evolves and unfolds in more than one country. For example, 3cm Less (2003) was shot between Palestine and Jordan, We Are All Fine (2005) was shot between Palestine and Lebanon and Always Look them in the Eyes (2007) was shot between Palestine and Jordan.

In 2013, I was tired of searching and attempting to reconcile with an image within a frame. I needed to escape this image with it’s problematic past and present. To rid myself of Palestine as a narrative, and to work with something that had nothing to do with this unbearable narrative of losses, I decided that I was going to make a film about one of the Arab world’s greatest Divas, Asmahan.

Asmahan was a Syrian Durze princess who would not let her aristocratic class tame her lust for singing. Instead she became a music icon of the Arab world during the 30s and early 40s. She was wild and emancipated and experimented in life as much as she experimented with music. It is said that during the Second World War, Asmahan became a spy for the English and then died a mysterious death in 1944.

Asmahan’s lust for life ,which made her presence unbearable to her class and many husbands, was supposed to help me in The Unbearable Presence of Asmahan (2014) to move forward and begin to formulate new kind of filmic narrative and theme.

The Unbearable Presence of Asmahan (2014)

I quickly realized that instead of escaping my previous image constructs and themes, I was actually transferring them onto Asmahan’s narrative.. I made Asmahan the queen of refugees, since she was born on a ship, while her mother was fleeing a marital dispute from Syria to Egypt. Asmahan grew up in Cairo, while spending her time between Lebanon, Syria, Egypt and Palestine.

In a road movie that begins in Egypt, then Lebanon and finally Vienna, I deconstruct the concept of icons in times of conflict. The film begins seventy years following the death of Asmahan, in Egypt, where an Arab Spring has flared only to be harshly crushed. This sets the scene to search for an icon, in times of conflict and change.

In The Unbearable Presence of Asmahan, I am drawn again to objects of memory, as I contemplate the effect of the loss of Egyptian cinema archives on our current present. When I visit the ruins of Studio Masar (Film Studio of Egypt) to document the disintegration of one of the most significant spaces for the creation of Egyptian cinema. The studio has been left to rot as the country struggles with corruption and military rule.

The Unbearable Presence of Asmahan, which seems to begin as a homage for a great talent, a woman, a refugee who was demanding to be seen the way she wished and not what was wished by the society around her, also encompasses an anti-hero narrative. In the opening sequence of the film, a young singer, who sees herself carrying a resemblance to the great diva, says: “You are nostalgic to the past, when you do not like your present.” This sets the nostalgic tone of the film, where nostalgia is seen as a form of escapism.

Shireen, the singer of today… (The Unbearable Presence of Asmahan, 2014)

As I finished making this film and as I watched it unfold in front of me on the big screen, I realized that I never escaped my constant search. Instead, my search, which embodies my restlessness and need for a resolution, a space, a home was prior to this film confined to Palestine, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon. Now it was expanded and widened to include Egypt and even Vienna. More spaces and more lands are now subjects for refugees dwellings. My need to reconcile with the archives and heal myself and my protagonists from a problematic past, also remained intact and drove the narrative of Asmahan.

Years ago, in a short video art piece The Place (2000), I had in my frame a woman at a cross road not knowing where to go. In her mind, there was a lust to return to where she once was, yet she feared that the place she is nostalgic to is no longer there. So she had a wish that time and space can be held still until she can leave this cross road. As I now review my work I realize that all my films were in one way or another a variation of what was depicted in this small video piece.

IN THE END

It was always the image that I was searching for. How do you form an image for a person who has been forcefully disconnected from their past and left to dwell in a problematic present. How can the present be depicted without reconciling with the past.

After this long journey of searching, and my attempt to escape what I was unable to resolve, I have now decided to confront my themes and narratives. No longer will I attempt to reconstruct the past. Instead, I am accepting that the past has vanished and that the equilibrium cannot be restored. I am not looking for a past image but for it’s present second life. I am reading and formulating an image from the present even if it comes from the past.

Azza El Hassan is a filmmaker and the winner of various international film Award such as The ALEPH AWARD, LUCHINO VISCONTI AWARD, and THE GRIERSON AWARD. She is the founder of The Void Project, which explores artistically and academically the effect of the abduction of Palestinian visual archives on the formation of a modern Palestinian visual narrative.