On the edge, balancing: Marion Scemama’s Relax Be Cruel

by Al Hoyos-Twomey

On the edge, balancing: Marion Scemama’s Relax Be Cruel

Marion Scemama’s Relax Be Cruel (1983-2023) is set amidst the ruins of downtown Manhattan’s once-bustling industrial waterfront, reduced to rubble in the wake of New York’s postwar economic decline. Shot on black and white 16mm film in the summer of 1983 (but not completed until 2023), Relax Be Cruel offers one of the only filmed accounts of the Pier 34 project (1983-84), the now-legendary takeover of a derelict Hudson River pier that was initiated in early 1983 by the artists Mike Bidlo and David Wojnarowicz. Seeking to escape the commercialism and competition that had begun to creep into the fledgling East Village art scene, Wojnarowicz and Bidlo invited their artist friends to join them in transforming this dilapidated, city-owned structure into a makeshift gallery and studio space. As word of mouth spread, more and more artists began venturing into Pier 34, filling its decaying interiors with murals, sculptures, installations, graffiti, and other site-specific interventions. Bidlo recalls that Pier 34 quickly became ‘the ultimate alternative space, where anybody could come and do almost anything they wanted, if they had the time, the energy, and the effort’. A series of photographs taken by Andreas Sterzing in the spring of 1983 not only capture ‘the romantic appeal of [the pier’s] ruinous state’, as Fiona Anderson puts it, but also the sense of playful camaraderie that prevailed amongst the first wave of artists who worked there.

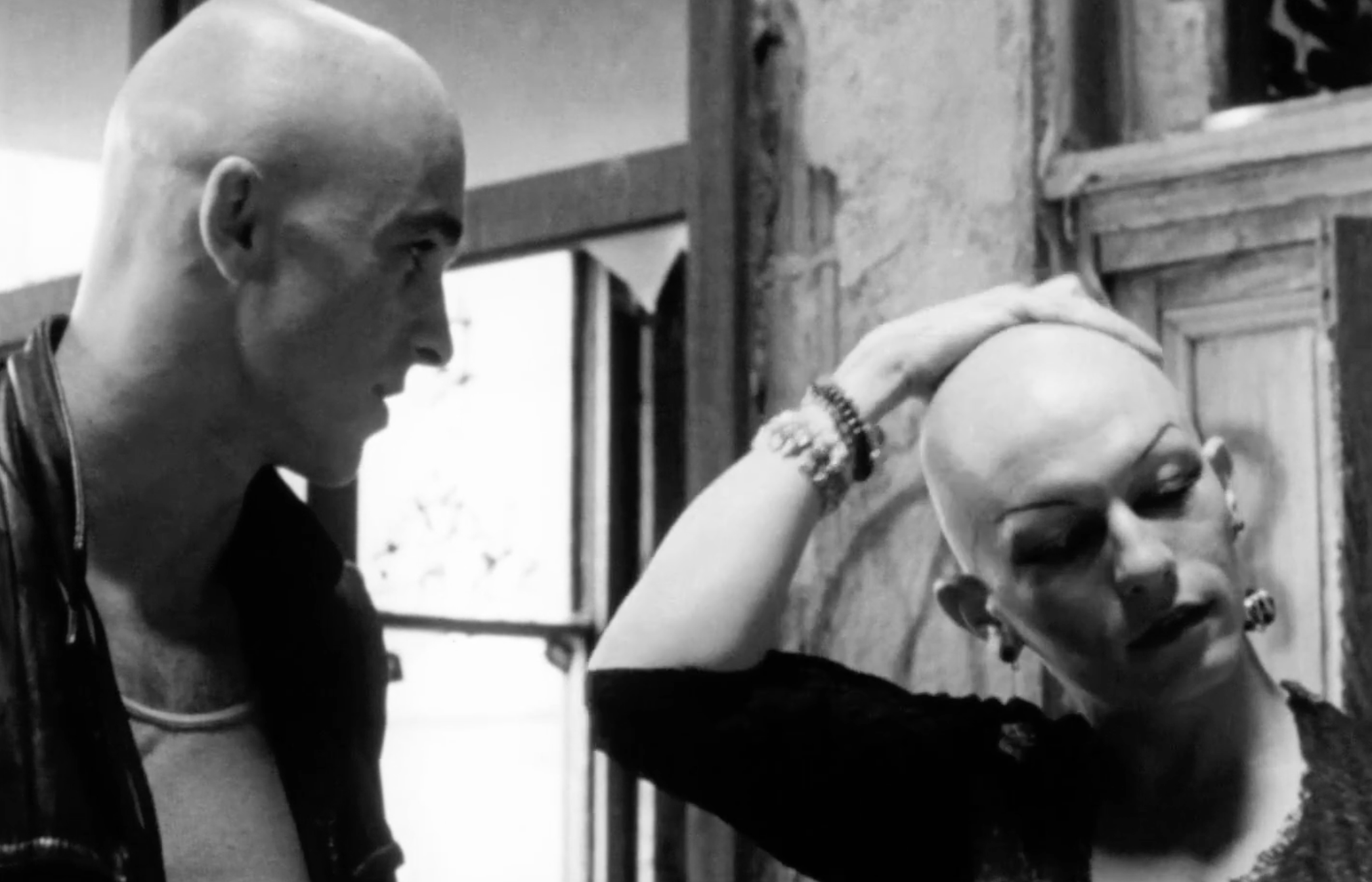

By the time Scemama arrived at Pier 34 in the summer of 1983, this collaborative ethos had begun to dissipate. As the scene became more crowded, artists started jostling for space, and work was painted over; by this point, many artists, including Bidlo and Wojnarowicz, had left in search of quieter waterfront sites. Relax Be Cruel captures the ambivalence of this moment, when Pier 34 appeared to be on the brink of a second obsolescence. Against a backdrop of junk-made sculptures and neo-expressionist murals (several of which have been partially covered with graffiti), the film follows an unnamed young punk as she spies on, chats to, fights with, or otherwise avoids the marginal figures who also haunt the pier, including anonymous cruisers, queer photographers, solitary performance artists, and other squatters. Comprising outtakes and unused rushes that were reassembled decades after the original working copy of the film was lost, Relax Be Cruel drifts from scene to scene, with each new encounter offering glimpses of the different communities who move through the space. Throughout the film, Scemama foregrounds Pier 34’s extraordinary materiality, lingering over its peeling walls, rotting floors, gaping windows, and the site-specific artworks that engage with these crumbling surfaces. Sound functions differently out here; the pier’s cavernous interiors amplify the tiniest internal movements, while muffling the omnipresent rumble of downtown Manhattan. As if to underscore the pier’s unique sonic character, the film ends with a car ride through a crowded, neon-soaked Times Square, whose propulsive post-punk soundtrack contrasts with the arrhythmic no-wave used for an earlier scene at the pier. In Relax Be Cruel, Scemama depicts Pier 34 as a site of tremendous creative vitality that is also a condemned space, ‘a place about death’, suspended beyond the everyday spatio-temporal rhythms of the city.

Scemama missed Wojnarowicz at Pier 34 that summer, but they were eventually introduced in late 1983 (a few months before the city demolished the pier). Almost immediately, Scemama recalls, there was ‘a connection, something really strong’ between them. Despite being unfamiliar with the artistic and cruising cultures that congregated in these sites, Scemama’s response to Pier 34 chimed with that of Wojnarowicz, who had been cruising and working in and around the piers since the 1970s. Like Relax Be Cruel’s main character, who describes a lifelong feeling of being ‘always on the edge, balancing’, the piers had long offered Wojnarowicz a space away from the alienation he felt as a queer working-class artist constrained within what he referred to as ‘this killing machine called America’. Wojnarowicz’s attraction to the waterfront as somewhere that was ‘as far away from civilization as I could walk’ echoes the film’s protagonist, who describes Pier 34 as ‘like being on the edge of the world, completely removed from society.’ In diary entries, poetry, and an array of artistic projects, Wojnarowicz explored the queer erotic life of the piers, and their remarkable material, temporal, and sonic qualities. For him, the waterfront was characterised by ‘a sense of unalterable chance and change, something outside the flow of regularity’, where normative experiences of time and space became irrelevant, and he could embrace ‘the sense of possibility in living life the way I’ve wanted to live it.’

In the decades since Relax Be Cruel was filmed, the Pier 34 project has become, in Scemama’s words, ‘emblematic of the boiling underground scene that exploded in the early 80s’, offering ‘the last space of freedom’ before HIV/AIDS and gentrification radically transformed downtown Manhattan, decimating both the experimental artistic practices and forms of queer and trans collectivity that flourished among the piers. To describe either Pier 34 or Relax Be Cruel as ‘pre-AIDS’ or ‘pre-gentrification’ projects, however, is not just to ignore the fact that these forces were already increasingly visible by 1983 (as a shot of John Fekner’s Health and Beauty Aids (On the Mezzanine) mural suggests). Such a periodisation also overlooks these waterfront projects’ complex engagements with time and space, which reflected what Anderson calls the ‘strange temporality of this ruined place’. Throughout their collaborative relationship, which was cut short by Wojnarowicz’s death from AIDS-related illnesses in 1992, Scemama and Wojnarowicz continually examined the artistic and political importance of ‘breaking down barriers, whether of time, or history, or spaces of delineations’. In Summer ’89 (1989-2021), for example, cutting-edge camcorder technology offers a way of compressing the linear process of filming, editing, and viewing a recording into a single action. In When I Put My Hands on Your Body (1989), physical touch between two men—an act made taboo by societal homophobia during the AIDS crisis—offers a conduit to the entire history of their bodies, from birth to death. As the closing scenes of Summer ‘89 make clear, Scemama and Wojnarowicz’s friendship was marked by a recurrent sense of being out of sync, with periods of intense intimacy punctuated by long stretches of estrangement. Viewed from the present, I like to think of Scemama’s Relax Be Cruel as a collaboration with Wojnarowicz across time and space: initiated months prior to their meeting, completed decades after his death, and animated by a shared desire to make sense of the liminal space-time of downtown Manhattan’s ruined waterfront.

~

Al Hoyos-Twomey is a PhD researcher in art history at Newcastle University. His research examines the role of cultural production in urban transformation, with a focus on the contested histories and geographies of Puerto Rican art and activism in New York’s Lower East Side in the 1980s.

To read this essay with footnotes, find the PDF version here: On the edge, balancing – Marion Scemama’s Relax Be Cruel