Passions represented a turning point in Muratova’s filmography, marking the final transition from more or less narrative films to ones where the plot is less important than the form, which is always free-ranging and exploratory. This film is her manifesto on the ‘unbearable emptiness of being’. While Muratova could be compared to Federico Fellini, this the only film in which she both reveals and simultaneously undermines the Felliniesque nature of her cinema.

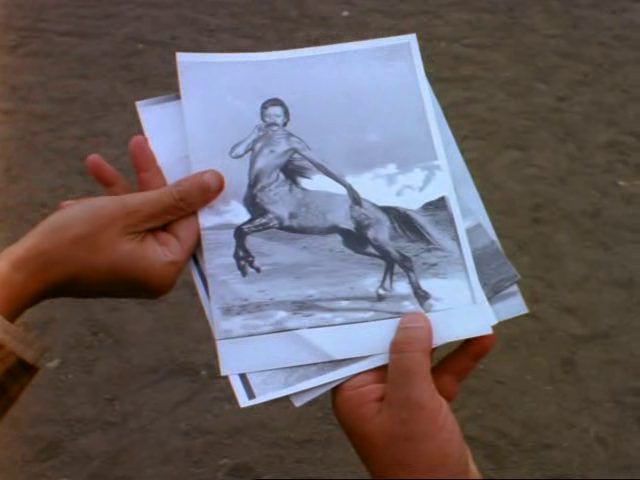

The film’s cheerily obsessive atmosphere, saturated and resplendent color scheme signalled a new direction and extension of Muratova’s sensibility even further into the pleasures of superficiality and the baroque acrobatics of theatricalised performance. Here she presents a cinematic world that spins out to follow each character’s passions down a rabbit hole of fabulation. In this sense, the film is a microcosm of Muratova’s cinema at its most fundamental—a play space, loosened in this moment by a renewed spirit of post-Soviet possibility. Muratova drew on horseman Boris Dediukhin’s memoir and shot at the Askania-Nova Soviet nature preserve, a location housing diverse creatures.

Nancy Condee, in her book The Imperial Trace, considers this film as a model of Muratova’s own “preserve,” her overarching filmic universe of human and nonhuman beings: “Muratova’s preserve functions as a similar imperial spectacle of diversity, a topsy-turvy, ecological imperium akin to the Friendship of the Peoples, wherein ‘each has his own mania’… Her compartmentalized eccentrics inhabit a zany All-Union Agricultural Exhibition, revealing social reality as a kind of Soviet zoo-state… Within this preserve, her most beloved eccentrics are those who, as she does, produce their own private art—most characteristically, bad art with no value other than its psychotropic effect.” —Elena Gorfinkel