The Name I Call Myself

Rejecting a catch-all definition of blackness while cast across two-screens, The Name I Call Myself unpicks multifaceted LGBTQ identities within the local black British diaspora. References to Audre Lorde and W.E.B. Du Bois’s idea of double consciousness permeate the film, inviting viewers to interrogate multiplicities of Black identity.

Programmer’s Note

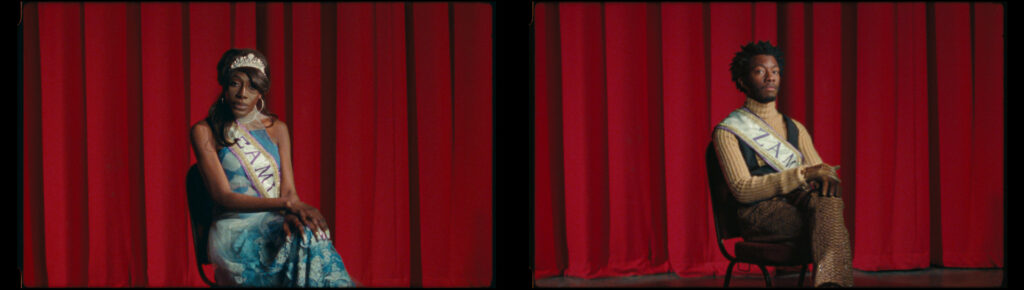

In this short by Rhea Dillon, the multiplicities of Black LGBTQ identities are carefully constructed and deconstructed, discarding the notion of a universal, homogenous experience of the world. Across two screens, Dillon shows a parent stretching in gentle yoga poses with their child; a group of friends having a meal in someone’s home; a person voguing outside alone; and later, inside, surrounded by peers, a couple holding hands in the back of a taxi. Small moments of affection that are a joy to witness.

References to Audre Lorde’s biomythogoraphy Zami: A New Spelling of My Name are peppered throughout and Dillon refers to W.E.B. Du Bois’s idea of double consciousness. The Name I Call Myself refuses to accept that identity can be codified or singular.

In an interview with Vogue, Dillon touches on the idea of Humane Afrofuturism—a term she coined to raze and rebuild notions of Afrofuturism. Dillon says, “I feel like there are practitioners right now, like Kerry James Marshall and Arthur Jafa, even designers like Grace Wales Bonner, who are elevating black people in an everyday sense. For instance, one of Kerry James Marshall’s super famous paintings is of a girl walking a dog down the street. It’s really just a girl walking a dog down the street, but why we’re marvelled by it is that the visual of a young black girl being so free in society has not existed until now, and that’s the problem.”

While her work is steeped in reality and research, there is also magic in Dillon’s frames. For the debut presentation of The Name I Call Myself, Dillon augments the screen to real life through a multi-sensory experience in collaboration with a fragrance from Byredo called Bal D’Afrique. The scent blends ingredients from Africa and Europe to pay homage to the diaspora of which these stories are being told.

Punctuating a soundscape by James William Blades, a voice echoes, “we are so many different ingredients”, reminding viewers to do more than just gaze beyond the binary—it asks them to dismantle it. It helps to transform the work into something beyond documentation, hitting an emotional register and inviting an active spectatorship. —Myriam Mouflih

Director Biography

Rhea Dillon (based in London) is an artist, writer and poet. Using video, installation, images, painting and olfaction, she examines and abstracts her intrigue of the “rules of representation” as a device to undermine contemporary Western culture. She is particularly interested in the self-coined phrase ‘Humane Afrofuturism’ as a practice of bringing forward the humane and equality-led perspectives on how we visualise Black bodies. Her work has been featured at a number of art and film institutions internationally, including The British Film Institute, 198 Gallery, Somerset House, Mimosa House, Blank 100 (London); Red Hook Labs, Aperture Gallery (New York); Red Bull Film Festival (Los Angeles); Sanam Archive (Accra, Ghana). She is an Associate Lecturer at Central Saint Martins (London) and the co-founder and curator of ‘Building The Archive: Thinking Through Cultural Expression’, a talk series that celebrates Black creative practitioners and their contributions to visual culture within arts and design higher education.

Director Filmography

The Name I Call Myself (2019), Process (2018), Black Angel (2018)