Izza Génini

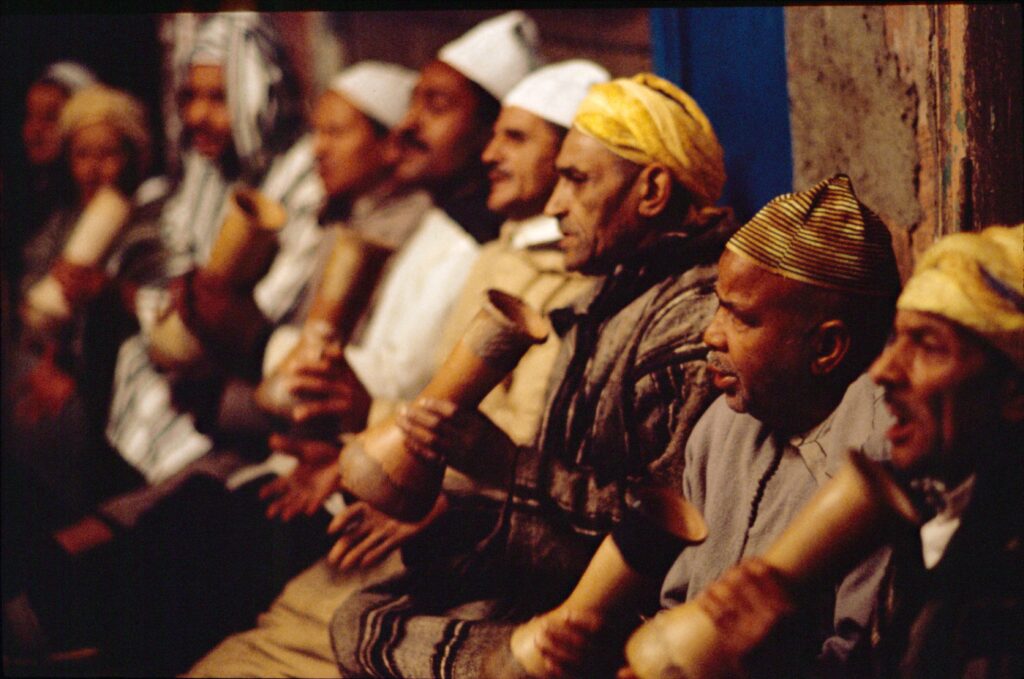

A pioneering woman in Moroccan cinema, Izza Génini’s practise sits solely within the realm of narrative documentary. As someone who was born in Morocco, grew up in France and returned there as an adult, her films grapple with themes such as diasporic identity and traditional Moroccan heritage, particularly focusing on the music of the country.

Génini’s relationship with film began through distribution, as she, alongside Louis Malle and Claude Nedlar, set up SOGEAV (now called OHRA), a distribution network for Moroccan films. Part of a generation of filmmakers finding a new language to communicate in a country where censorship was rife, she began producing films in the late 1970s, most notably Ahmed El Maanouni’s documentary Trances (1981), following the influential Moroccan band Nass El Ghiwane. King Hassan II’s ascension to the throne marked the beginning of what some now called the Years of Lead – a time of great political upheaval and difficulty in the country, where freedom of speech was near impossible. Artists and filmmakers therefore grappled with the role culture and media played in representing a nascent state.

Although Génini might posit that her films are not political, their existence is pushed against King Hassan II’s vision of cultural and religious unity in Morocco, and show people practicing religions other than Islam and communities of different heritage living together harmoniously. She portrays ways of living beyond the modern city and represents rural space and the countryside without romanticising it, often prioritising the perspectives of women in these spaces. Her films capture Moroccan tradition and custom, seen through the eye of someone whose identity straddles both France and Morocco, a push and pull between a country recently made postcolonial and the country who colonised it.

In a chapter on Génini in her book, Negotiating Dissidence, both Dr Stefanie Van de Peer and Génini note the complex relationship some Moroccans had with their own culture:

During the French Protectorate, Génini explains, many educated Moroccans, including herself, turned their backs on their own culture, preferring instead to direct their gaze towards France. ‘Like others in my generation I rejected Moroccan culture because I thought it was inferior to the French. Our dreams of emancipation were directed towards the West’ (Hillauer, 2005: 349). When she finally started to look back at Morocco, she experienced an emotional reconnection with the country’s musical heritage.

It is this emotional connection that shines through in Génini’s films. She has spoken about her filmmaking practice as being geared towards instinct and feeling, and this can be clearly seen in the vivacious energy of her films. Her presence shines through, showing a familiarity, but with an excitement that is almost infectious. —Myriam Mouflih