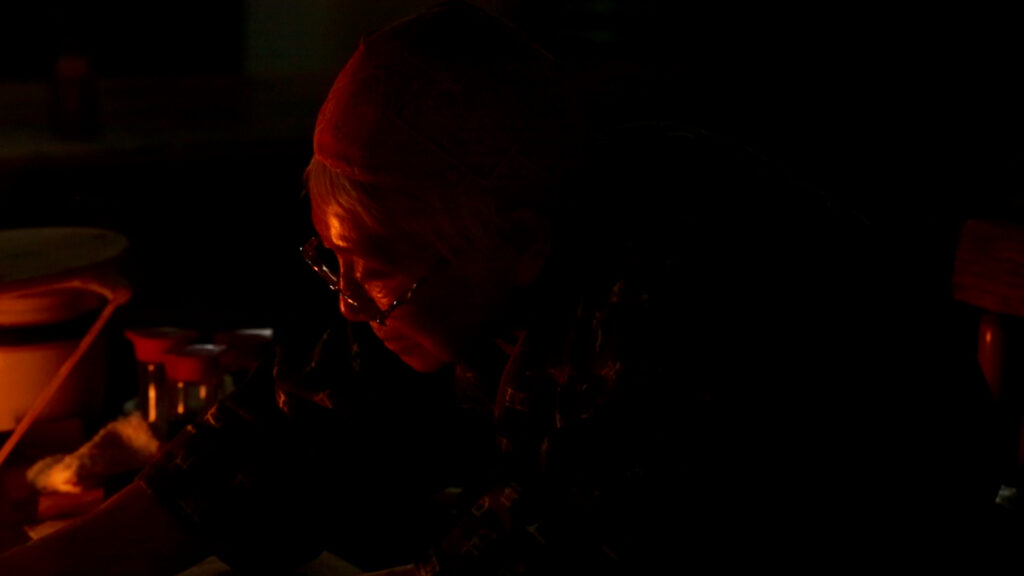

Without dialogue or narration, Araki’s film sumptuously captures all manner of delectable foodstuffs in the slow, focused state of their preparation as well as their consumption. The griller works with patience and tenacity, with liquids lightly simmering on the tops of seashells or within the caps of upward-turned mushrooms. A dull, constant din of low noise is punctuated by the occasional pop of charcoal. While most of Fuel is framed in close-up and mid shots, Araki filmed the images with maximal social distance from the far corners of the restaurant with a long telephone lens, preferring to capture its atmosphere and the performance of the chef observationally, with as little intrusion as possible.

The film is densely packed with subtext and symbolism that far outstretches its short running time. While on a research trip to Hokkaido, the artist was recommended to dine at Kushiro Robata-yaki and found the restaurant’s central hearth reminiscent of the structure of cise houses built by the indigenous Ainu peoples who originally populated that region. Though these indigenous people and their culture have shamefully been made invisible over past centuries—a sadly parallel situation to Native Americans in the United States—Araki posits that perhaps less tangible elements have been unconsciously passed down across generations. The central hearth in Ainu cise houses was a place for family to gather, share stories, eat and carry out sacred rituals, and perhaps this has informed the structure of this old, authentic robata-yaki restaurant.

Fuel skilfully reflects the motif of this central hearth and the sustaining importance of fire to humans, both in the specific case of this restaurant and as a symbol to be found across cultures and histories. The film progressively builds towards a key scene wherein its second prominent character, the Sapporo-based artist Satoshi Hata, devours the food set before him following a hand gesture deriving from the Ainu worship known as onkami. Hata’s onkami is partial and incomplete, signifying the loss of this culture across generations of Ainu culture—as the artist’s matrilineal ancestors may have Ainu roots. Rather than representing this indigenous culture as an outsider himself, Araki wishes to point to the limits of what he might be able to understand as a Waijin—rather than an Ainu—himself. —Herb Shellenberger