Crisis news is a genre film: On resistance, news cycles, and the banal time of protests in Tiffany Sia’s ‘Never Rest/Unrest’

by Amy Lea

Program

Crisis news is a genre film: On resistance, news cycles, and the banal time of protests in Tiffany Sia’s ‘Never Rest/Unrest’

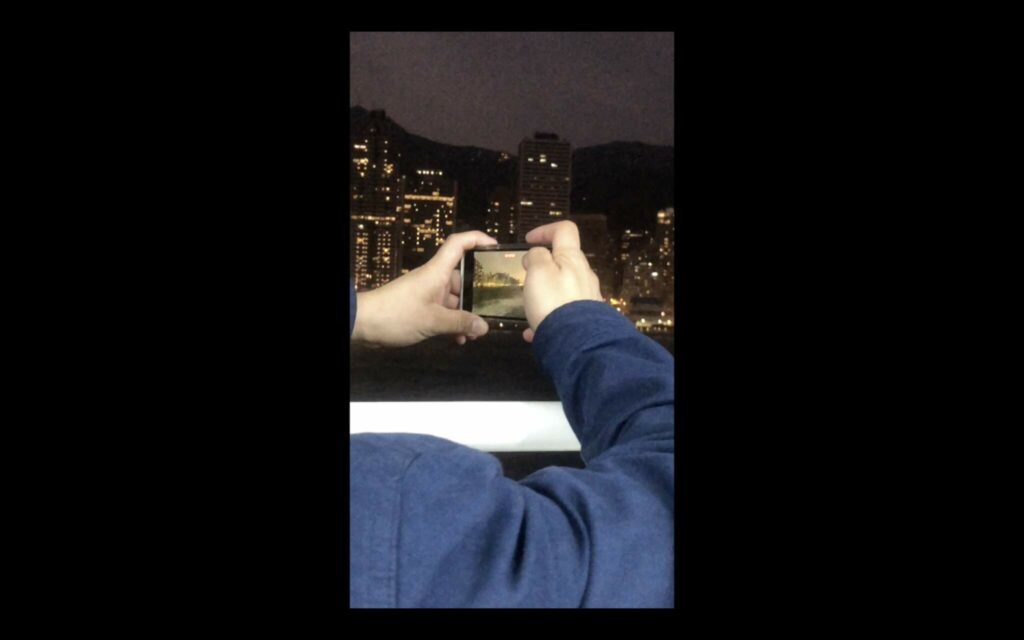

Still from Tiffany Sia, Never Rest/Unrest (2020)

Never Rest/Unrest (2020) is a short documentary by Hong Kong-based artist Tiffany Sia comprising on-the-ground footage of the anti-government protests that occurred in Hong Kong throughout the latter half of 2019. For Sia, who is used to working with text-based art in zines and on social media, this is a first foray into filmmaking, but it is by no means a timid one. So clearly enthralled by her artistic vision, Berwick Film and Media Arts Festival chose to present Never Rest/Unrest as part of a single-film presentation for their most recent edition of the festival.

Filmed in portrait on a mobile phone, the visual language of Never Rest/Unrest instantly calls to mind the distinctly modern form of video-watching many of us engage in through social media. The symbolism is deliberate—social media has been instrumental in the past decade in spurring political activism, as much of our news is now gleaned from outside the mainstream media, from people on the street capturing and sharing live footage to their online networks. This was certainly the case for the Hong Kong protests, and much of Sia’s footage reflects this. She features shots of people scrolling through crowdsourced maps on their phones, protestors holding up phones to record demonstrations, the rapidly moving chat of livestreams and social media posts. This is contrasted with the traditional news cycle: footage of mass arrests playing on the subway and small groups of onlookers watching clashes between protestors and police on public television screens. In these shots we see the familiar 16:9 aspect ratio of the mainstream framed in portrait, and a clear line of demarcation between the footage of the protestors and that of traditional media. Sia’s stance on the two differing narratives surrounding political events is apparent. It lines up with her citing Julio Garcia Espinosa’s 1969 essay ‘For an Imperfect Cinema’ as an important provocation for the film. In the essay Espinosa advocates for filmmaking to be taken out of the hands of the elite and into those of the masses; that “the new outlook for artistic culture is no longer that everyone must share the taste of a few, but that all can be creators of that culture.” This seems no better reflected today than in a film comprising mobile phone footage.

Another aspect of Espinosa’s call to action was about putting an end to the artistic tradition of solely identifying “seriousness with suffering.” It is easy to see how this comes in to play in the Hong Kong protests, with violent images dominating the international media coverage. Such images are used to sensationalise, and Sia is more than aware of this. As she writes in ‘Too Salty Too Wet 更咸更濕: The Leak as Discharge’ (provided in accompaniment to the film), “crisis news is a genre film,” more interested in depicting cinematic events than reality. Sia resists this in the film, as dramatic scenes of protest are intercut with calmer moments. We see the slow movements of flowing water, buskers playing in the street, a resting animal in a zoo enclosure. Even moments of resistance shown—crowds gathered at night for a candlelit vigil, orderly marches in the rain, graffiti spray-painted up an escalator—are often not the dramatic outbursts readily circulated by conventional news. These are the less ‘exciting’ moments of a political protest, what Sia describes in the synopsis as “often banal time.” The back and forth between the rest and the unrest, the dull and the newsworthy, is simply a reflection of reality, and Sia’s form of fighting the edited news cycle, enabled exactly by the technology that allowed her to make the film.

This resistance to editorialising in Never Rest/Unrest has a powerful impact on spectatorship, as the film purposefully does not try to explain itself to those outside Hong Kong. Subtitles are omitted, rendering it hard for the foreign viewer to pick up on much of the cultural and political nuance in the scenes. Yet this overwhelming specificity and locality has the effect of situating the film on a global scale; without an understanding of the full story being told, the viewer sees patterns being formed instead. It is easy to connect the overarching movements with similar protests happening all over the world: the chanting crowds and marches could be from the recent pro-democracy protests happening in Thailand; the clashes between civilians and police mirror the Black Lives Matter protests in the United States throughout much of 2020. This creates a film whose meaning is heavily dependent on the perspective of its viewer, what Sia alluded to, in the ‘in conversation’ event for her film’s screening, as being akin to an optical illusion showing two different images at once depending on how your eyes focus. The end result is a film that, impressively, explains nothing while clearly getting its message across, and suggests Sia’s first film will likely not be her last.

Amy Lea

Amy Lea is a project coordinator and curator based in Edinburgh. As part of her Master’s degree in Film, Exhibition & Curation from the University of Edinburgh, she has co-programmed screenings for Glasgow Film Festival and Edinburgh International Film Festival, and since gone on to work in the event management side of both festivals as well as others in Scotland and North East England. Amy has also been a submission viewer for several festivals across the UK.