Too Salty Too Wet 更咸更濕: The Leak as Discharge

by Tiffany Sia

Program

Too Salty Too Wet 更咸更濕: The Leak as Discharge

Too Salty Too Wet 更咸更濕: Leak as Discharge is an excerpt of Tiffany Sia’s forthcoming book Too Salty Too Wet 更咸更濕 to be released later this year. The work is a sequel to Salty Wet 咸濕 published in 2019 by Inpatient Press, which is in the Asia Art Archive as part of the collection of print materials relating to the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill protests. Released for Berwick, this excerpt is a companion to Sia’s short film Never Rest/Unrest. The “consensual leak” is a retelling of geography that takes aim at the notion of the spectacular.

///

When I wrote “Hong Kong is the first postmodern city to die,” it was in March 2019, three months before the protests began. It was a tweet. When it was published in Salty Wet, some saw it as a prescient vision, while others reacted with incredulity (Do you really think so?), defensiveness (Hong Kong is not dead, we will still live here) and defiance (Hong Kong will fight on). In the tradition of writing poems while gazing at the moon, intoxicated, I was with J▇▇ and A▇▇ at the time, walking to make the ferry before the sunset, and tipsy. It was especially smoggy that day and the light diffused against the wet pollutant particles and cast burning colors reflected against slick buildings sprayed by the mist of light rain. Meant as a provocation, when the line came to me and I tweeted it out, it merged three thoughts at the time. I will tell them here in three sections. I also took this picture:

(1) The Centerfold

Hong Kong peaked during the height of the postmodern era in the 1980s and 1990s. As the harbor city at the center of global trade, it was the busiest container port in the world between the years of 1987 to 1989 and from 1992 to 1997 (and also between 1999 to 2004). 1

During those years, the Pearl River Delta was the channel through which the most material goods in the world passed. Viewed through the lens of design and material history, Hong Kong was the city at the cusp of a world’s supply chain during the ramp up of globalization.

While Hong Kong culture itself has been written about as what Hong Kong historian Ackbar Abbas describes as an “elusive subject” in perpetual disappearance, Hong Kong’s material culture expresses its irrefutable and visible imprint on the world through its industrialization. 2 To tell Hong Kong through the lens of design and material history is to tell the city, and the Pearl River Delta, on its own material terms.

Central design offices may have been in metropoles like London, Paris or New York in the 1980 and 1990s, but Hong Kong was a site of liaison—adapting sketches and ideas into serial production and material form. Placing Hong Kong and the Pearl River Delta in history as the nexus of global industrialization also reimagines design as a geographically dispersed and global process. In his essay, ‘Early Modern Design in Hong Kong,’ Matthew Turner writes, “the economic strategy of this region was characterized by first, a labor-intensive system of serial or mass production; second, a strong export orientation; and third, a process of adaptive design.” 3 The Pearl River Delta, Turner continues, was “the crucible for export designs that adapted the world’s goods to Chinese materials and manufacture,” even dating back to the tenth and nineteenth century.

Hong Kong as a global nexus also bears a history of violent exchange. The special territory was established as a new crown colony as a result of the Opium Wars between Britain and China, and as historian Lisa Lowe describes, the territory satisfied the colonial mercantile strategy towards “the expansion of British imperial sovereignty in Asia,” based on “liberal ideas of ‘free trade’ and ‘government.’” 4 The Pearl River Delta was also a site for trafficking drugs and coolies. As Hong Kong historian Christopher Munn states, “two great trades sustained Hong Kong’s early economy: the import of opium into China, and the export of labor out of China.” 5 Coolies were captured and sent to the Americas, “shipped on vessels much like those that had brought the slaves they were designed to replace.” 6 Centuries in the making, Hong Kong, as a special territory established by liberal free-trade principles, ushered the dark trade of opium and human trafficking from the colonial era to the industrialization of textiles and objects for worldwide consumption in globalization.

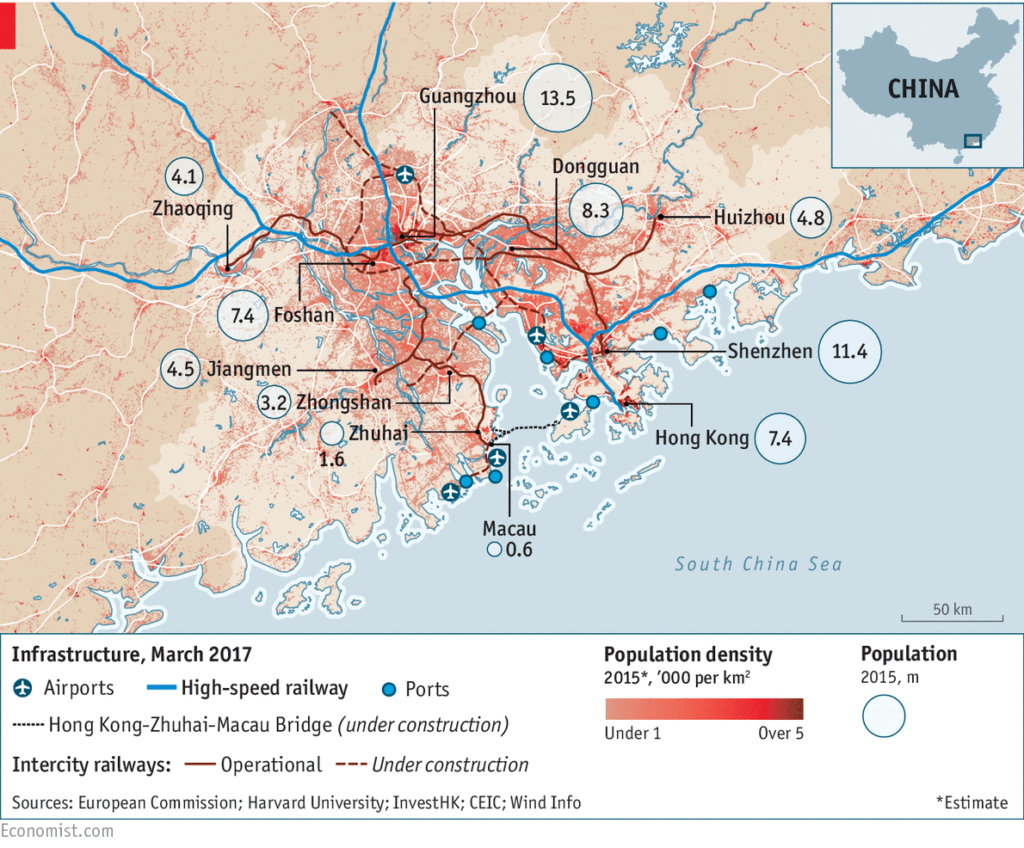

Map of the Pearl River Delta 7

The Pearl River Delta is the material birthplace of globalism, and on a map, it even looks like a cunt. A dirty joke lies in this map. Look at it one way and you see the Pearl River Delta. Look at it another way and you see a cunt. Look at it another and you see the Greater Bay Area. Hong Kong was always built for extraction.

(2) Salt to Taste

Crisis news is a genre film. As Hong Kong’s rule of law unraveled rapidly throughout these months, the events here became a spectacle that captured the front pages of newspapers around the world. Flaming barricades, umbrellas open against teargas, the stream of blue from a water cannon against small cowering bodies, and green lasers shooting across the foreground of the Hong Kong skyline made for sensational pictures. News-making took on cinematic proportion. Compelling images of political crisis had in them the power to hold attention from observers of far away, and Hong Kong, in the scale of international media, eclipsed news in other places such as Xinjiang, Haiti, Chile, Iran and Puerto Rico, which were concurrent to the Hong Kong protest timeline. What was exceptional about Hong Kong taking over international news in the latter half of 2019 and beyond drew headlines not because it exceeded the level of violence in other places—it did not—but it featured a central position in geopolitical arcs such as the trade war. Perhaps that is what was so enduring about the fall of Rome in the historical imagination: it is indeed a rare moment in history that we get to watch a city of this scale—of cultural hold in the global imagination and of great financial capital—die. Hong Kong and its relation between empires lubricated the conditions for political entropy to enter into the realm of the spectacle.

Cities have died throughout history. To say it inversely, empires have laid cities to waste. “Salting the earth” is the idiom of desecrating conquered cities and to render land arid and uninhabitable. It is said that the Romans killed Carthage this way, but this is untrue. “Salting the earth” is, as Ronald T. Ridley describes, a mere “contamination” from the history of other places, lesser known in our contemporary imagination, of ancient cities of the “near East” such as places like Hatussa, Arinna and Hunusa that were killed in ritualistic fashion. 8 These places, when captured and destroyed, were sewn with minerals and plants, including cress, sipu and kudimmus, salt-like in their composition, to erode and henceforth curse these places’ hopes for future reinhabitation. Unlike Carthage, these ancient cities have been overlooked in the catalog of the popular imagination, and although these examples are in the Middle East, these geographies are part of a global mythos of dead cities. To be sure, Hong Kong will be habitable, but for a place where people have historically sought political refuge, for whom the city is habitable, it will change. It used to be a privilege to leave, but for those already in exile, it is a privilege to stay.

The ongoing political crisis makes a sinister point about the times we are entering that most people who are displaced from cities, killed, jailed, disappeared or forced into exile, cannot resist the exception to this rule of being forgotten along the timeline of history, who have few or no witnesses. Perhaps it is hubristic to claim that we can live on, that we demand witnesses, for especially now, so many populations die in secret and face such conditions without such attention. To look upon history, or other places in the world, is but a vision to relativize our present.

Today, if a city that is the fourth single largest stock exchange in the world can unravel, Hong Kong presents a riddle about the tight relationship between capital and crisis. 9 I used to think that capital would protect a city from falling into political crisis, but in fact, it invites powerful spectators. From the people who fly in for dark tourism, the financial institutions who are shorting in the background, real estate groups speculating the consequences on the global luxury real estate market—Hong Kong is dying and its death became capital. In Afflicted Powers: Capital and Spectacle in a New Age of War, writing on the relationship between the state and the technics of the image of September 11, Iain Boal and other authors assert, “states can behave like maddened beasts, in other words, and still get their way. They regularly do. But the present madness is singular: the dimension of spectacle has never before interfered so palpably, so insistently, with the business of keeping one’s satrapies in order.” 10 So while the valleys felt by the luxury real estate market forced investors to dump properties and seek luxury real estate elsewhere—multi-billion dollar blockbuster IPO’s continued to make splashes on the Hong Kong stock exchange. Deng Xiaoping famously assured the public before the handover that, “horses will still run, stocks will still sizzle, dancers will still dance.” In a time of political uncertainty, it is telling that this statement to the public is aimed mainly at investors, and this political talking point bore Hong Kong’s essential and its only lasting post-handover promise: Hong Kong is the site for spectacle and capital, and this is how the city will be consumed.

(3) Salting the Earth

Hong Kong’s special status was inevitably going to end by or before 2047. To say Hong Kong will die is to read a historical “use by” date that loomed over us all, foretold by its legal architecture as a special territory. To call it a death was also to invoke lawmaker Claudia Mo’s statement from 2016, when the two pro-democracy lawmakers, Baggio Leung and Yau Wai-ching, were disqualified from Parliament for their subversive swearing-in ceremony: this was “the beginning of the end of Hong Kong.” 11

It matters who calls it the end, or a death. When political pundits outside of Hong Kong did so, their claims echoed notions of a territory lost on a geopolitical map. Between the years of the Umbrella Movement and 2019, I eavesdropped on foreign correspondents, who left in pursuit of other bureaus, lamenting their work had dried up, There’s no story left here anymore. The past year proved them wrong. But at the time, these off-the-record statements sounded like a threat: when the inevitable end would come for Hong Kong as a special territory—if as a slow death—would it not be spectacular enough for the news? When others from afar claimed that Hong Kong was dead, I was frustrated with their implicit foreclosure of the need to look on.

To name a death demands that this place be seen when spoken by those who live it. On May 18th, 2020, pro-democratic lawmakers were pulled out of the legislative council by force for the vote on the anthem law. Some called it a coup. Claudia Mo tweeted, “a perfectly illegal meeting. A perfectly illegal election. Used to say it’s the beginning of the end for Hong Kong. Now we’re not just near the end, we are at the end.” 12 These calls resound as if pleas for attention. When remarking on the death or end of Hong Kong, we want witnesses.

These times demand that we reframe our assumptions about crisis narratives. At the very least, they demand that we rethink so-called normalcy, or how the notion of peacetime has or could have ever existed in a colony or postcolony. Handed over from British rule, the teargas flag system endured as one of the defining rituals of violent policing in Hong Kong. A flash of flags before teargas firing and shooting of projectiles (if they even bothered to give warning beforehand): the British followed this procedure in the ‘67 riots in North Point, and the Hong Kong police continued its legacy. 13 This symbolic mirroring between colonial and postcolonial political order repeated itself in legal warfare, such as with the reinterpretations of Basic Law, dissolving of the separations of power and the conflicting, simultaneous definitions of Hong Kong as separate but also part of China. Using lawfare aggressively expressed what a bureaucratic, puppet government knew best—obsessive, meticulous, intentionally oblique dealings of assaults and obfuscation through fine print. Lawfare was meant to bore and exhaust, and every piece of new lawfare that made the news required a lag in time, waiting for a legal expert to weigh in.

When the mask ban was invoked in Hong Kong, it was through a loophole in a colonial-era emergency ordinance. In times of trying to make sense of living through ongoing crisis through lawfare, we may be “tempted to look to the writings of Carl Schmitt” imperial law historian Lauren Benton states, “and the related theories of Giorgio Agamben” to understand the invocation of emergency measures. 14 But Benton takes aim at these state of exception frameworks as an oversimplification, especially in a colonial context. It is beginning here, we must forge nuance when discussing crisis and colonialism. The emergency ordinance, even during the colonial era, was criticized as draconian. Henry Litton, the former secretary of the Hong Kong Bar Association’s committee, foreshadowed in 1968 exactly the law’s vulnerability to exploitation. In a letter to the Times in 1968, he wrote, “the evil of the Emergency Regulations is that it leaves to the benevolence of the Hong Kong government to observe the basic principles of the rule of law without making it a legal requirement.” 15 The appeal was unsuccessful, and the emergency ordinance was carried over into Basic Law of Hong Kong after the handover. Measures of political repression, such as a mask ban, are subsumed in a system of law that carried forth a colonial legacy, and the legal warfare put these systems into sinister motion. It was only a matter of conscience, as thin as a “paper door” (to borrow the words of Martin Lee, nicknamed the “father of democracy” in Hong Kong) to invoke de facto martial law.

The postcolony bears the imprint of its former shell. Colonialism can be compared to corporate entities, to use an uneasy set of metaphors. They go through mergers and acquisitions. They migrate systems from one holding to another. They are clever and cunning at using fine print. And they are experts in the tactics of obfuscation. Functioning in remote offices, the leadership of viceroys is at its most effective as bureaucratic. There are many components of the old order that remain intact, from Basic Law, to the teargas warning system to the more innocuous forms like the city’s sidewalk design. Lawfare in a postcolony illuminates how “histories of imperial law tell another story…” contrary to the state of exception—that colonial law, as Benton imagines it, is a warped landscape and timeline of “overlapping, semi-sovereign authorities within empires [generating] a lumpy juridical order.” 16 This juridical “lumpiness” expressed in examples such as the mandatory mask wearing for COVID-19 compounding the ongoing mask ban. Examples such as this go on, and take on even more sinister forms, as specters of legal terror, that this text intentionally speaks around. Lawfare was how Hong Kong met its “death by a thousand cuts.”

In other terms, “death” possesses the potential to germinate a radical reframing of history. “Apocalypse” originates from the Greek word, literally meaning “an uncovering.” In filmmakers Adam Khalil and Bayley Sweitzer’s science-fiction thriller, Empty Metal, a voiceover by an Indigenous character posits, “the end of the world, on the other hand, is a matter of perspective. Most people think the end of the world is going to come for everyone at the same time. For us, the end of the world happened a long time ago.” In identifying with the language of Indigenous and Black liberation, to call this “the end” demands that we animate our historical oppression into a means of agency, to see our struggles as entangled with other timelines. The settler-colonial mercantile economy unfurls as a series of receipts, and historian Lisa Lowe tells flows of this supply chain: “…fabrics woven, dyed, and painted in India and China were exchanged for African slaves shipped to the Americas, and those in which opium, grown, processed, and packaged in India, was exchanged for Chinese workers sent around the world.” 17 Along with the genocide of Indigenous peoples to take their land, these economies mapped bodies, labor and goods onto a seabound continuum of colonial capital. This distinction not only tells our pain in its magnitude—that this is the end of Hong Kong—but it is also to see this city as part of a global colonial historical timeline of apocalypse in sequence.

Apocalypse is manifold and concurrent. It is uneven among populations around the world. It is police states. It is borders. It is concentration camps and so-called “re-education” camps. It is pandemics, and governments that allow by negligence and incompetence pandemics to kill its people. It is legal warfare. It is ecological collapse. To invoke Achille Mbembe, they are circumstances upon which people live under the status of non-humans, and as the “living dead.” 18 It is not that the apocalypse only happens to some populations—but rather, that some groups, and nations, afford to buy more time in our expiring world. “If we feel that things are calm,” Jasbir Puar asks, “what must we forget in order to inhabit such a restful feeling?” 19 In maintaining the “restful feeling,” what must those who live outside these “end worlds” do to afford this forgetfulness? What we afford in forgetfulness, do we claim also the right to kill by literal and systemic means? In Hong Kong, the postcolony lives on as a specter: As an RTHK broadcaster said in 2014, “there was a time when we lived in Hong Kong. Now we live in a place called Hong Kong.” 20

From a colonial entrepôt to a special economic zone, Hong Kong was a constructed territory for extraction at the nexus of transnational economies, spanning a timeline of shifting world orders. As the proverbial serpents of this axis mundi asphyxiate this city, Hong Kong the postmodern nexus, unravels as a node in the balance of global finance. That these conditions that are able to lay waste to a global city could arise out of any financial center, the “death” of Hong Kong is but one of many cities to come. The fall of metropoles in the age to come guarantees this in its pattern: that capital makes entropy spectacular, and the spectacle is a weapon.

///

My Uncle B▇▇▇ once said, “Hong Kong has always been a controversial place ever since I was a kid. Many external factors in the world converge on this small place. It eventually matters.”

///

///

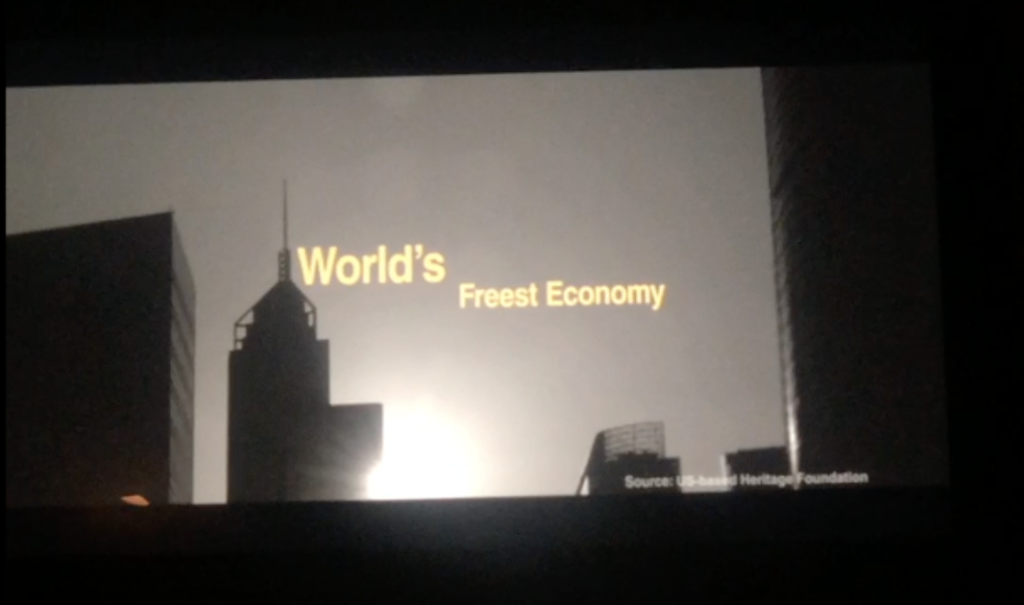

It was only in a very recent past that the Hong Kong skyline was synonymous with global finance, and was often used as a visual shorthand in advertisements related to banking or travel. “Hong Kong: Asia’s World City.” I remember watching an ad on the plane when I was en route from Hong Kong to ▇▇▇ in June, feeling the serrated edge of that shift.

///

I stopped getting my period at all since I had an IUD, but in those months I experienced breakthrough bleeding often and observed a rusty discharge on my panties. Intense menstrual cramps gripped my uterus, and my lower abdomen felt as if it contained a liquid substance simultaneously boiling and gurgling inside of me. My friend D▇▇ asked me in the fall if I had experienced any problems with my “M,” a Cantonese colloquialism referring to menstrual periods. “I ask because, P▇▇’s friend who’s also been out there a lot, exposed to teargas, has been noticing some strangeness with her cycles. I was wondering if you had experienced the same.”

A year after that conversation with D▇▇, I came across an article by Physicians for Human Rights in Bahrain from 2012. 21 It detailed the consequences of toxic chemical agents on reproductive systems, including abnormal menstrual periods. The report quoted a nurse at Salmaniya Hospital who asks, “there are many, many miscarriages. We believe the miscarriage rate has increased, although there is no quantitative evidence. What I want to know is: What is this gas… and what will be the future complications?” 22

///

///

- “Vessel Arrivals by Ocean/River and Cargo/Passenger Vessels,” Hong Kong Marine Department, 2020. https://www.mardep.gov.hk/en/publication/pdf/portstat_1_m_a1.pdf

- Abbas, M. A. Hong Kong Culture and the Politics of Disappearance. University of Minnesota Press, 1997. 25.

- Clark, Hazel, et al. “Early Modern Design in Hong Kong.” Design Studies: A Reader, Bloomsbury, 2013. 22.

- Lowe, Lisa. The Intimacies of Four Continents. Duke University Press, 2015. 99.

- Christopher Munn, “The Hong Kong Opium Revenue, 1845–1885,” Opium Regimes: China, Britain, and Japan, 1839–1952, ed. Timothy Brook and Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000. 105–126.

- Lowe, The Intimacies of Four Continents. 24.

- “What China can learn from the Pearl river delta,” The Economist, April 6, 2017. https://www.economist.com/special-report/2017/04/06/what-china-can-learn-from-the-pearl-river-delta

- Ridley, R. T. “To Be Taken with a Pinch of Salt: The Destruction of Carthage.” Classical Philology, 81, no. 2 (1986):140–6.

- “HKEX Fact Book 2018,” Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing, 2018. https://www.hkex.com.hk/-/media/HKEX-Market/Market-Data/Statistics/Consolidated-Reports/HKEX-Fact-Book/HKEX-Fact-Book-2018/FB_2018.pdf?la=en.

- Boal, Iain A., et al. Afflicted Powers: Capital and Spectacle in a New Age of War. Verso, 2005. 37.

- Claudia Mo, “This is the beginning of the end of Hong Kong,” The Guardian, November 7, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/nov/07/this-is-the-beginning-of-the-end-of-hong-kong-china.

- Claudia Mo. Twitter Post. May 18, 2020, 1:19 PM. https://twitter.com/claudiamcmo/status/1262251352178098178.

- “Vanished Archives: A Documentary on Hong Kong’s 1967 Riots,” Zolima Citymag, 2016. https://zolimacitymag.com/events/vanished-archives-a-documentary-on-hong-kongs-1967-riots/.

- Benton, Lauren A. “Bare Sovereignty and Empire.” A Search for Sovereignty: Law and Geography in European Empires, 1400-1900, Cambridge University Press, 2011. 282.

- Gary Ka-wai Cheung, Hong Kong’s Watershed: The 1967 Riots, Hong Kong University Press, 2009. 85.

- Benton, “Bare Sovereignty and Empire.” 290.

- Lowe, Lisa. The Intimacies of Four Continents. Duke University Press, 2015. 84.

- Mbembe, Achille. Necropolitics. Duke University Press, 2019. 92.

- Puar, Jasbir K. Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times. Duke University Press, 2017. xxvi.

- Yuen Chan. Twitter Post. August 28, 2020, 9:17 PM. https://twitter.com/xinwenxiaojie/status/1299335268508594176

- Physicians for Human Rights, Weaponizing Tear Gas: Bahrain’s Unprecedented Use of Toxic Chemical Agents Against Civilians, August, 2012. https://www.thenation.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Bahrain-TearGas-Aug2012-small.pdf

- Ibid.

Tiffany Sia (Hong Kong) is an artist, writer, filmmaker and independent film producer, based between Hong Kong and New York. She has spoken at Studio Voltaire (London), Printed Matter, Cooper Union, The New School (New York) and Tai Kwun Contemporary Art (Hong Kong). She is committed to multidisciplinary works with a focus on new narratives, diasporas and indigenous voices. She graduated from the Film and Electronic Arts program at Bard College and has been the recipient of a Fulbright scholarship. She is the founder of Speculative Place, an experimental, independent project space hosting resident working in film, writing and art in Hong Kong. Sia is the author of 咸濕 Salty Wet, a series of anti-travelogues on distance and desire within and without Hong Kong published in July 2019. Her experimental short film Never Rest/Unrest takes the form of a hand-held cinema about the relentless direct action in Hong Kong from early summer to end of 2019. The work takes up the provocation of Julio Garcia Espinosa’s “Imperfect Cinema” on the potential for anti-colonial filmmaking, resisting spectacular documentary and news narratives. Instead, crisis poses ambiguous, anachronistic and often banal time.